Stretcher.org

Stretcher.org is-was an online publication that provides a voice to the visual arts and culture in the Bay Area, while connecting with creative communities internationally. Currently, the publication is only periodically updated and serves more as an archive.

The idea for Stretcher grew out of a recurrent conversation between Megan Wilson and Glen Helfand. They recognized a lack of Bay Area visual art publications that provided broader critical discourse on art and its connection to other cultural disciplines (politics, economics, personalities, and socio-cultural phenomena). They decided to create a publication that would address this need. Amy Berk, Andy Cox and David Lawrence were invited on board to help create the initial framework for Stretcher and were later joined by Ella Delaney, Cheryl Meeker, Tonita Abeyta, and Meredith Tromble. The first year of development saw several transitions, including the departure of Cox to pursue personal projects and Wilson’s 8-month leave to also complete outside projects. Stretcher.org was launched on June 5, 2001. Wilson continued to work with Stretcher as an editor and contributing writer through February 2002. Stretcher continued to thrive and transform under the direction of Amy Berk, Ella DeLaney, David Lawrence, Cheryl Meeker, and Meredith Tromble. The publication was updated regularly with new reviews, essays, artists' projects, and updates from around the world until 2015.

Stretcher reunion dinner, 2014 L->R: Meredith Tromble, David Lawrence, Cheryl Meeker, Glen Helfand, Megan Wilson, and Amy Berk

Wilson’s archived articles on Stretcher include:

The Gentrification of our Livelihoods: Everything Must Go…, published 2014

We Lose Space / You Lose Culture, Megan Wilson and Gordon Winiemeko, San Francisco Art Commission’s Grove Street Gallery, 2000

Preface: When I began researching and writing The Gentrification of our Livelihoods in early March 2014 one of my primary interests was the impact that the collaboration between Intersection for the Arts and developer Forest City’s creative placemaking 5M Project is having on the existing communities that have invested in and called the South of Market home prior to the tech booms. Having worked with many community-based organizations within the SoMa community for the past 18 years, I’ve had deep concerns about the development’s impact for the neighborhood and its impact on the future of Intersection.

However, I would not have predicted the announcement that Intersection made on May 22nd to cut its arts, education, and community engagement programs and lay off its program staff would come as soon as it did. What began as a reflection on the shortcomings of creative placemaking as a tool for economic development and its implications on gentrification and community displacement has become a cautionary tale for arts and community organizations to question and better understand the potential outcomes of working with partners whose interests are rooted in financial profit.

Over the past two months I’ve spoken with many of the stakeholders involved with the 5M development, as well as the creative placemaking projects that are helping to shape the changes in the culture and landscape throughout San Francisco, these include: Deborah Cullinan, former Executive Director, Intersection for the Arts; Jamie Bennett, Executive Director, ArtPlace America; Angelica Cabande, Executive Director, South of Market Community Action Network (SOMCAN), Jessica Van Tuyl, Executive Director, Oasis For Girls, April Veneracion Ang, Senior Aide to Supervisor Jane Kim, District 6 and former Executive Director of SOMCAN; Tom DeCaigney, Director of Cultural Affairs, San Francisco Art Commission; Bernadette Sy, Executive Director, Filipino-American Development Foundation (FADF); Josh Kirschenbaum, Vice President for Strategic Direction, PolicyLink, and an anonymous source within Forest City Enterprises.

I recommend reading the in-depth interviews with the majority of these participants. Their input helps to augment and present a fuller understanding of the complexities, concerns, and possibilities of the stories and information provided in the article. Please click on the links below to read:

Deborah Cullinan, Executive Director, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, former Executive Director, Intersection for the Arts

Jamie Bennett, Executive Director, ArtPlace America

Angelica Cabande, Executive Director, South of Market Community Action Network (SOMCAN)

Jessica Van Tuyl, Executive Director, Oasis For Girls

April Veneracion Ang, Senior Aide to Supervisor Jane Kim, District 6 and former Executive Director of SOMCAN

Tom DeCaigney, Director of Cultural Affairs, San Francisco Art Commission

CONTINUE READING …

Selamat Datang! Welcome!, published 2002

PDI Lookout Stations, Bali, Indonesia, 2001, Photo Credit: Megan Wilson

Last spring I decided it was time for a travel adventure — something a little more challenging than weekend camping. It had been nine years since I’d ventured out alone into the unknown and spent six months driving through Mexico and Central America. It was the most incredible experience I’d had — before and since. The question now was where to next? I’d always wanted to go to Southeast Asia, having spent my early twenties in Eugene, Oregon, where it was practically a rite of passage to travel East to "find yourself" (or cheap imports that you could bring back and sell at a 500 percent markup). I was still interested in going there, but for different reasons; now I was more curious to find alternative art communities and learn how national and international politics and global consumer culture had affected the region.

Indonesia was particularly appealing for this reason. I couldn’t recall having ever heard anything about the country’s contemporary art scene. I also knew that the political climate had been incredibly tense over the past several years with the forced resignation of Mohamed Soeharto in 1998. In addition, Bali is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world, making it fertile ground for seeing the effects of global consumerism on a third-world nation. So Indonesia it was.

I did as much research as I could beforehand; however, the pickins were slim with regard to contemporary culture outside of consumer interests (gamelan, traditional dance, shadow puppetry, and so on). But as luck would have it, a friend was able to connect me with Dan McGuire, a contributing writer to Latitudes who has lived in Indonesia. Dan provided with me a number of alternative resources. I learned that many people in Indonesia speak some English due to the high number of English-speaking tourists the country hosts each year. With this information and a Lonely Planet guide in hand, I arrived in Denpasar on July 3, 2001.

Las Vegas of the South Pacific

My first stop was Ubud on the island of Bali. Touted as the cultural center of Bali, it’s an hour's drive north of Denpasar, inland and still fairly south on the island. It’s made up of several main streets, most prominently Monkey Forest Road, that run for a couple of kilometers with many little roads interconnecting. It’s very beautiful, yet in a seemingly staged way — a combination of Club Med, Las Vegas, and Rodeo Drive (yes, they have Polo and Prada boutiques) in the South Pacific. Everything seems to revolve around the tourism industry. Even when I encountered beautiful temples, I found myself questioning whether they were real or just another prop erected to provide island allure. Each interaction also appears to be determined by the protocol of perceived customer and the exchange of money. The question, Where are you from? is asked not out of genuine interest, but instead as a way of sizing up how much you can afford and at what price to start the barter. This is followed by the next question, How much you pay? applied to anything that you’ve purchased — accommodations, drivers, goods. What soon became apparent is that tourism is now The Culture on Bali — it is everyday life. Traditional dances, rituals, and crafts are still practiced daily, but with the purpose of pleasing a foreign audience to collect foreign currency.

Many Famous Artists

While having breakfast at my hotel on my third morning in Ubud, I was approached by a rather suave, long-haired Balinese man dressed in a pair of nice khakis and a T-shirt that said "Seattle" on it. He looked to be in his late twenties or early thirties. I learned that his name was Royan and that he worked as a guide and driver for the hotel. He, as I’d come to expect, first asked where I was from and then what I did for a living. I told him that I’m an artist and writer. He then told me he’d be right back. He returned with a thick book full of loose "paintings" of traditional Balinese images, ranging in style from very detailed, like etchings, to looser forms and lines. He told me that he, too, is an artist and that he’s the descendent of a very famous Balinese artist. At the bottom of each painting, he was careful to point out his name. He asked if I was interested in buying some of his works. When I told him that I’d think about it, he moved on to asking if he could take me out to the countryside — away from Ubud — for $40. I offered $20. We agreed to meet the following morning. Later that day, I saw the exact same "paintings" in several different shops all with different names signed at the bottom. I asked one woman who had painted them and she replied that her husband had.

Megawilson Meets Megawati

The next day, Royan and I headed out to explore the area surrounding Ubud. Fields upon fields of tiered rice patties lined the landscape on such a massive scale that it felt surreal to actually be there amidst terrain that was so familiar through postcards and commercial images.

As we drove I noticed what appeared to be bus stops — elevated platforms partially enclosed with bamboo walls and thatched roofs — many spray-painted red and black with graffiti of a horned creature and the tags "Pro Mega" and "PDI." I realized what those horned heads depicted when I saw the image of a very sinister-looking bull painted on the side of a house with the letters PDI placed above. I asked Royan about the graphic images and learned that this evil-eyed steer is the symbol for the PDI party (Democratic Party of Struggle) and is synonymous with then-vice-president Megawati Sukarnoputri (known simply as Megawati), daughter of Indonesia’s first president, Ahmed Soekarno. I learned from Royan that 90 percent of Bali residents are supporters of the PDI and they love Megawati. I was also told that the presumed bus stops were actually lookout posts that had been built by the party during the violent uprisings that led to the 1998 resignation of then-president Mohamed Soeharto.

The ubiquitous graffiti and the lookout stations reflect the tense political climate that has erupted over the past five years in Indonesia. The country has been witness to extreme turmoil and violent disruptions prompted by a severe economic crisis nationwide and a civil war on East Timor that resulted from the Timorese vote for independence from Indonesia. In addition, the last three years have seen four presidencies, including the forced resignation of Abdurrahman Wahid while I was there on July 26 and his replacement by Megawati.

CONTINUE READING …

Review: Tiara Dame Ruth Sirait: Sweet Lolly, published 2002

Sweet Lolly (2001), Tiarma Dame Ruth Sirait, Photo by Megan Wilson

Kedai Kebun Gallery

Yogyakarta Indonesia

July 5 - 30, 2001

When I told people that I was going to be traveling in Indonesia for five weeks this summer, the response rarely deviated from two thoughts of mind. Those a bit familiar with the country through the occasional news report would ask, “Aren’t they having some sort political problems there?” (To which the answer is an emphatic “yes.”)

The second sort of reply I heard came from those who had visited the country (Lonely Planet guide in hand) and offered “the shadow puppets, Ramayana Ballet, and Gamelan are amazing.” However, when I’d mention that I was actually more interested in Indonesia’s contemporary alternative art scene and perhaps the influence that the country’s political tension has had on the work being made there, the unanimous response was “Do they have an alternative art scene?” I wondered the same since I couldn’t recall ever having seen or read anything about contemporary art in Indonesia, but I was determined to find out.

I flipped through my ten-year-old collections of Artforum, ArtNews, and Art in America, scouring both features and the review sections for a headline reading “Indonesia,” which proved to be fruitless. Research on the Web produced an academic history of Indonesian art over the last 30 years — one that reflected interests and trends throughout the art world during the same period (a rejection of modernism in the ‘70s, a booming market in the ‘80s, and a heavily post-modern approach in the ‘90s). I also found several essays specific to Indonesian concerns, mainly the struggle between embracing and rejecting Western influence on their contemporary art. However, nothing I came across gave me a sense of what is happening NOW.

As is often the case, my best source came from a ‘friend-of-a-friend’ who had lived in Indonesia and as luck would have it, is a contributing writer to Latitudes Magazine, the best resource for contemporary culture in Indonesia. Through Dan’s connections, I was able to find a thriving alternative arts community in Yogyakarta (pronounced Jogjakarta) on the island of Java.

“If you are going to Yogya your first top should be the Cemeti gallery on Jl. Parankritis. These folks are the foundation of contemporary and media art in Yogya.” This was what I wanted to hear. So following Dan’s suggestion, I stopped in at the Cemeti, where I was welcomed with ginger candy and an invitation to sit down and hear about the city’s contemporary arts community. Program Directors Alsyah Hilal and Sudgud Dartanto presented me with several binders of slides from their past exhibitions and I was struck by how similar the art in Yogyakarta was to work being created in San Francisco, yet with a clear identity of its own. In addition, Hilal and Dartanto gave me a list of alternative spaces I should check out.

As I walked into the Kedai Kebun Gallery to see Tiarma Dame Ruth Sirait’s installation, Sweet Lolly, I had no idea what to expect from a show with that title by a young Indonesian artist and fashion designer, in a third-world city known for batik.

CONTINUE READING …

Nattering with members from the former Apotik Komik, published 2002

Talking with three members of the artists’ collective Apotik Komik in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2001, L->R: Arie Dyanto, Bambang Toko, Megan Wilson, and Popok Tri Wahyudi

Apotik Komik was an artists’ collective based out of Yogyakarta in the nineties, who created work in response to the political and social conditions of Indonesia during that decade. Apotik Komik was: Arie Dyanto, Samuel Indratma, Bambang Toko, and Popok Tri Wahyudi. Today the artists still create work from the same socially/politically-driven approach, however, each works individually.

Megan Wilson What exactly was Apotik Komik?

Apotik Komik Apotik Komik was a visual community living and working in Yogya [in Indonesia]. Collectively we made work in public spaces – alternative spaces outside of the gallery that we found – empty walls, billboards.

MW Did you guys get permission to use the spaces that you worked on?

AK Not always, and we did get in trouble with the government at times, which led to the design of "official" uniforms that we’d wear when we made our public work.

MW Sort of like guerrilla actions?

AK Yes, exactly, these were guerrilla actions.

MW What kind of materials would you use when you did your work, and did you ever use spaces that already existed and alter them – like billboards?

[The group exchange sideways glances and laughs.]

AK Yes, much of our work — then and now — is about this type of play, working with irony and subversion instead of trying to hit people over the head with a message. Our work is political and comments on social conditions here, but it’s not meant to be a direct political action or protest. We want it to be subtle and humorous – poking fun at tradition. We often use plywood or cardboard and house paints because the materials that artists normally use, like – canvas and oil or acrylic paints, – are very expensive here. And we like the idea of using these alternative materials and the idea that they’re temporary until destroyed. We also make comic books, … individually and collectively.

MW When did you guys start working together – and how did Apotik Komik start?

AK It started in 1992, however we began to get a lot more visibility in 1997 with a show that Samuel (Samuel Indratma is the fourth member of Apotik, who was unable to be at the interview) organized at his house called Apotik Komik. It took place on the day of the general election and was risky because the government had associated our group with the PRD (Democratic People’s Party), which is outlawed here and they were keeping a watch on us. It was a group show and used the wall of Samuel’s house with the theme of "flying."

MW So what happened?

AK It was very successful and got a lot of attention from the art community and from the press (private television companies – (RCTI, SCTV and Anteve, the National broadcast TVRI) – and several printed media (– BERNAS, Kedaulatan Rakyat dailies and Panji Masyarakat magazine.).

MW That’s great that you had such support.

CONTINUE READING …

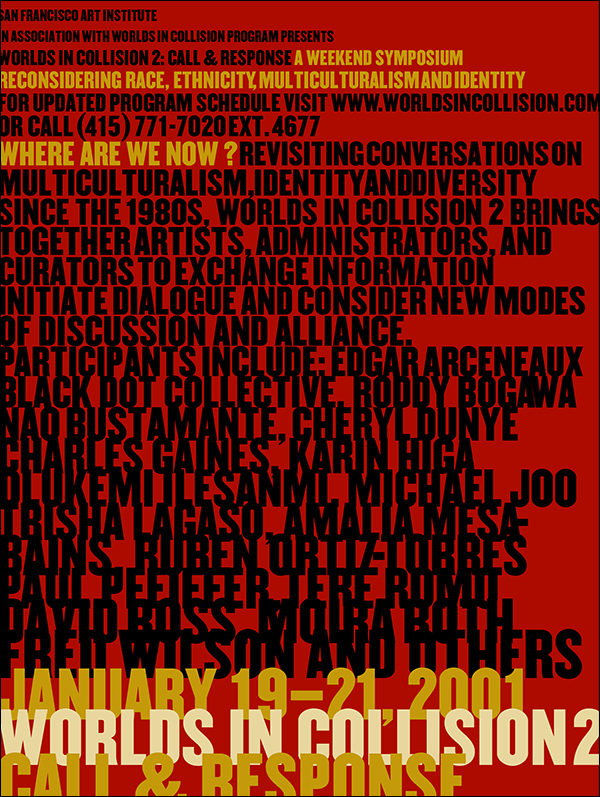

Worlds In Collision at SFAI, published 2001

Worlds In Collision, SFAI, 2001

“What I’d like to add are some reflections on the effects of symposia generally- on us as artists, on shaping a community, on how they can act as an invisible connective tissue through a place, artworks, community policy. That’s ultimately what’s interesting about them, is that they exist ephemerally and pass into unconscious levels of thought, or lore and legend- they have a slippery effect.” – Ella Delaney

When Ella first approached me to write a companion piece to her review of the Deleuze conference at CCAC, I meditated on this concept of symposia. The word conjures up images of privilege and staid, sterile environments. I pictured an auditorium filled with people who would be offended if a paperback were to graze their inlaid oak bookshelves, or who would sip on chilled French white wine while discussing French theory. But I knew that this initial reaction was as shallow and narrow as the people I envisioned filling it.

Instead I turned to the notion of an organized community gathering and the sharing of ideas. Based on this, the first symposia that I’d attended were the rodeos that I’d go to with my family as a kid growing up in Montana. Every year we’d pack up our god-awful gold station wagon and drive an hour from Billings to Red Lodge for the 4th of July, listening to Waylon and Willie as we wove our way through Big Sky country. The Home of the Champions Rodeo was a three-day event that included a parade each day, a “mutton busting” contest for which kids would be placed on sheep, wriggling and giggling as the clock timed how long the little dogies could ride it out, and the rodeo itself which featured bareback, saddlebronc, calf roping, team roping and steer wrestling (among others.) Folks from all over the West and beyond would converge on the small town to take part in the festivities and exchange tips and stories that ranged from who was breeding the best lineback dunns (yellowish brown horse with a black line running down the spine) to recipes for baked beans. It was a way of sharing information with others while having a hell of a lot of fun and showing off the best cowboys, cowgirls and rodeo stock in the country.

While a weekend of buckin’ broncs and pootin’ ponies is a very different experience from an arts-related symposium, when a similar grassroots community spirit pervades it, there is great potential for impacting social change and policy. The structured setting also creates a safe environment for disparate groups to share and exchange potentially unpopular viewpoints, discussing sensitive subjects such as race, gender and sexual identity.

Worlds in Collision 2: Call & Response was an inspiring and provocative weekend long symposium co-organized by faculty member Carlos Villa and curator Eungie Joo that reconsidered race, ethnicity, multiculturalism and identity at the San Francisco Art Institute January, 2001. The 3-day event grew out of a discussion that began at the school over 25 years ago. In 1976, Villa organized the bicentennial exhibition, Other Sources: An American Essay. The show, which included theater, dance, music, food, and visual art, represented one of the first local efforts to challenge the American canon of art within the contexts of multiculturalism and community. This historic occasion was followed by four symposia that took place within a three-year period at the Art Institute during the late eighties. The discussions and debates that transpired led the Art Institute to institutionally recognize multiculturalism as a complex and critical topic that students believed was missing from their education. As a result, the Worlds In Collision course was added to the school’s curriculum in 1989. Villa developed the course, introducing alternative perspectives and models for understanding art and art education. Guest artists and activists from various Bay Area communities were asked to visit and speak about their art and their communities, their ethnicity and their culture.

CONTINUE READING …

Review: Sophie Calle: Public Spaces - Private Places, published 2001

eruv (1996), Sophie Calle

The Jewish Museum

San Francisco

March 7 - June 28, 2001

TGrowing up, my hero was Phil Donahue. I was fascinated by the social/political nature of his shows, the personal interview format and his ability to bring highly controversial and often taboo subjects such as transvestites and incest to the mainstream public. In essence, the same could be said of French artist Sophie Calle whose performative work is the highbrow version of the talk show tabloid mixed with a dose of Candid Camera. Calle herself often alternates between probing host and vulnerable, tell-all guest/subject.

For over 20 years she’s toyed with the lines between public and private as voyeur and provocateur, testing these limits long before ‘reality shows’ such as Big Brother, The Mole and Survivor were ever a possibility. Calle’s most notorious and naughty work has included the stalking and photo-documentation of strangers, who became the unsuspecting subjects of her obsessive ritual.

The captured moments were later displayed with Calle’s collected observations as a photo-text installation. In a similar piece performed in 1983, Calle found an address book on the street. She returned it, but not before calling each of the phone numbers listed to gather information on the book’s owner. She then published their perceptions of him in the French newspaper, Liberation. Such disturbing and impish acts have rightfully earned Calle the title of ‘Bad Girl’ in the art world. However, as surveillance and shock have become commonplace, Calle has both matured and raised the ante in her recent work.

Her exhibit, Public Spaces - Private Places at the Jewish Museum explores the boundaries of space in Jerusalem, a city bitterly divided by claims to its sovereignty. In this investigation, Calle considers the metaphoric borders created through the Orthodox Jewish tradition of erecting an eruv.

The eruv is a physical and symbolic enclosure created by stringing galvanized steel wire from poles in and around a Jewish community. This practice is used as a way of stretching the Talmudic law that prohibits the transfer of objects outside of the home on Sabbath (every Friday at sun down until the following day at sun down) by defining the space within the eruv as “home.” The ritual of honoring the eruv is quite involved and in Jerusalem it includes a weekly assessment by an “eruv inspector” to insure that the lines have not been damaged. If any gaps are spotted, the repairs must be completed before the beginning of Sabbath, otherwise an announcement is made by rabbis throughout the city that the space is not protected.

Twenty panels of black and white photographs of Jerusalem’s eruv line the walls of the gallery, symbolically recreating the sacrosanct space. Calle also asked fourteen residents of the city, both Israeli and Palestinian, to take her to public places they consider private and share their personal associations with the sites. Their stories are documented anonymously through framed 4x6 photos and text (one 8 _ x 11 sheet each) that have been placed atop a map of Jerusalem in the center of the gallery. Due to their size it is unclear if Calle was attempting to connect the stories and images with their actual geographic placement on the chart, though it seems likely. The narratives reflect the complexities and contradictions that accompany the notions of territory and “other,” as well as reveal the seemingly banal, yet ineffable memories experienced by everyone:

At first I was attracted by the bucolic appearance of the olive groves and terraced landscapes; the contrast between the pastoral images, full of gentleness that might have inspired Poussin, and the harsh, political, tribal reality;

There is nothing specific, nothing particular about that spot; just an accumulation of experiences and memories. This is where you learn, in the street, that’s how you’re shaped.

The most powerful and provocative impression was left by Calle’s contextual frame for these personal images, and specifically the memories of Palestinians presented within the heavy and profound symbolic borders of the Jewish eruv. I could feel my own edges being pushed by this choice of position and the subtle betrayal implied. Yet this is the strength of Calle’s work—her ability to evoke and challenge our innermost limits of human experience and behavior, surreptitiously invading and helping to redefine our own internal spaces.

Also on view at the Museum are several pieces from Calle’s earlier pursuits: The Sleepers, 1979, for which she invited 29 guests to sleep in her bed while she photographed them; The Blind, 1986, documentation of interviews conducted with people who were born blind and asked to share their images of beauty; and The Autobiographical Stories, an ongoing series of photographs paired with text that overtly focus on the artist as subject. These selections help to give viewers unfamiliar with Calle an introduction to her prior work. However, as segments of larger projects they lose some of the intrigue and poignancy generated by her complete installations, such as The Eruv.

Sophie Calle: Public Spaces - Private Places

The Jewish Museum

March 7 - June 28, 2001

121 Steuart Street (between Mission and Howard Streets), San Francisco

Sun. - Thurs. 12p.m. - 5p.m. (415) 591-8801