Strangers for Ancestors #11: The Missouri Mormon War

Reprint by Chas. W. Carter 1886 of photo of a drawing Extermination of L.D.S. from the State of Missouri in 1838 Published by S. Brannan, Prophet's Office, New York.

In the last entry, my great, great, great, great grandfather Bradley Barlow Wilson Sr., his wife Sarah Smith, their seven sons Whitford Gill, George Clinton, Guy Carlton, Henry Hardy, Lewis Dunbar, Bradley Barlow Jr., and Bushrod Washington and their families had all moved from New York to Richland, Ohio setting up homesteads for each family next to one other. In 1836 they were visited by Mormon missionaries Oliver Granger and George Albert Smith, who convinced them to join the Mormon Church, which had been formed by Joseph Smith in 1830 in New York. The entire family was baptized into the Church on May 23, 1836.

As noted in the previous post, my ancestors’ baptism in the Mormon Church represents an important point in my Wilson family’s history. This decision would direct the trajectories of the next four generations in ways that reveal the cycles and impacts of Manifest Destiny’s trauma, violence, and addiction, and the resulting resistance, resilience, and voice to speak truth to power.

And this is where we pick up ….

Missouri

Stains Series: Tinney Grove, quilling (paper craft) on paper, 9” x 9” unframed, 12.5” x 12.5” framed, 2021

In October 1836, Bradley Barlow Wilson Sr., Polly Gill Wilson, and their seven sons and families moved from Ohio to Missouri where they settled at a place known as Tinney’s Grove, 20 miles southeast of Far West, where the Mormon Church had set up their headquarters. In the winter the families built cabins at Tinney’s Grove. The land that included Tinney’s Grove and Far West was stolen by these settler colonizers, my family included, from the tribal peoples of the Hopewell Culture, Mississippian culture, Kansa, Osage, Otoe, and Missouri.

On August 6, 1838, the Missouri Mormon War began following a brawl at an election in Gallatin, resulting in increased organized violence between Mormons and non-Mormons backed by the Missouri Volunteer Militia in northwestern Missouri. The Battle of Crooked River in late October led to Lilburn Boggs, the Governor of Missouri, issuing the Missouri Executive Order 44, ordering the Mormons to leave Missouri or be killed. On November 1, 1838, Joseph Smith surrendered at Far West, ending the war. The Mormon followers left the area in a long line of wagons traveling eastward back over the long miles they had come a few years before, described as “a sorrowful, poverty stricken procession.” They wandered across Missouri to the banks of the Mississippi River, opposite of Quincy, Illinois where thousands arrived. Whitford Gill Wilson stayed behind at Tinney’s Grove. In an excerpt from the church biography of Mormon Elder George A. Smith, the cousin of Joseph Smith who baptized the Wilson family with Oliver Granger, it was noted “Elder George A. Smith & companion Don Carlos Smith (younger brother of the Prophet Joseph Smith), missionaries in Missouri in the year 1838, having walked all day and part of the night with no place to stay till two in the morning when they came to the door of Whitford Gill Wilson of Tinney Grove, and were welcomed in to stay the night, to warm their chilled bodies, and were fed by members of the church.”

Smith had been charged with treason following his surrender, but escaped custody and fled to Illinois with the remainder of the Missouri Mormons. The migration from Missouri to Illinois continued as noted in the following excerpts from George A. Smith’s biography:

“During the months of February and March of 1839 the chilly winds of winter howled about them and added to their discomfort. Many died from the exposure and fatigue of the journey.”

“By April 1839 15,000 saints had left Missouri. They traveled the three hundred miles in six weeks and had lived in the open air in all kinds of weather. The saints huddled together along the banks of the Mississippi River, some had tents, and some made dugouts, but most were in the open air. Sickness was everywhere, here Joseph and Hyrum Smith found them.”

“Joseph [Smith] arranged to buy two hundred acres of swampy land at Commerce, Illinois just forty miles north of Quincy. It was at this time that malaria struck the saints, and many were healed by God’s power through the Prophet Joseph Smith, who was worn out and sick himself but arose from his bed and called upon the Lord in prayer and healed the sick in a marvelous way through the power of God. In a few years, the swampy land at Commerce was transferred into the City of Nauvoo the beautiful and a white limestone temple on the hilltop in the center of the city was being built. Beautiful homes lined the broad streets, and everyone was busy.”

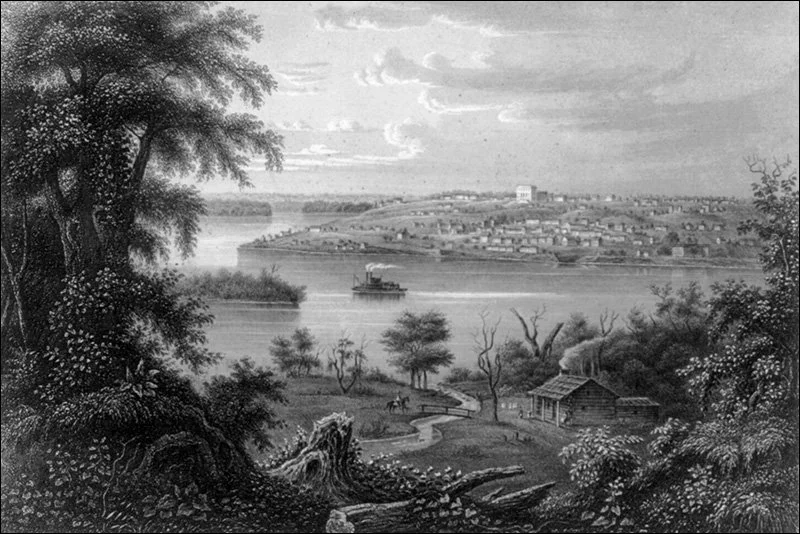

Bird's-eye view from hill, across water to Nauvoo." Engraving of Nauvoo, Illinois, ca 1855

The land that Joseph Smith named Nauvoo in 1840 was stolen from the Sauk and Fox peoples by the settler-colonizers.

The United States and its Policies of Genocide, Property Theft, and Total Subjugation

excerpts from Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States

While Joseph Smith was developing, drafting, and implementing his scheme for a new religion, President Andrew Jackson was carrying out the original plan envisioned by the country’s founders, and in particular Thomas Jefferson, to engineer the expulsion of all Native peoples east of the Mississippi to the designated “Indian Territory.” as noted by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz in her book An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States; she continues:

“As Wilma Mankiller, the late Cherokee principal chief wrote in her autobiography:

The fledgling United States government’s method of dealing with native people — a process which then included systemic genocide, property theft, and total subjugation — reached its nadir in 1830 under the federal policy of President Andrew Jackson. More than any other president, he used forcible removal to expel the eastern tribes from their land. From the very birth of the nation, the United States government truly carried out a vigorous operation of extermination and removal. Decades before Jackson took office, during the administration of Thomas Jefferson, it was already cruelly apparent to many Native American leaders that any hope for tribal autonomy was cursed. So were any thoughts of peaceful coexistence with white citizens.”

It's not that Jackson had a "dark side," as his apologists rationalize and which all human beings have, but rather that Jackson was the Dark Knight in the formation of the United States as a colonialist, imperialist democracy, a dynamic formation that continues to constitute the core of US patriotism. The most revered presidents Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln, Wilson, both Roosevelts, Truman, Kennedy, Reagan, Clinton, Obama-have each advanced populist imperialism while gradually increasing inclusion of other groups beyond the core of descendants of old settlers into the ruling mythology. All the presidents after Jackson march in his footsteps. Consciously or not, they refer back to him on what is acceptable, how to reconcile democracy and genocide and characterize it as freedom for the people.

…

“During the Jacksonian period, the United States made eighty-six treaties with twenty-six Indigenous nations between New York and the Mississippi, all of them forcing land sessions, including removals. Some communities fled to Canada and Mexico rather than going to Indian Territory. When Sauk leader Black Hawk led his people back from a winter stay in Iowa to their homeland in Illinois in 1832 to plant corn, the squatter settlers there claimed they were being invaded, bringing in both Illinois militia and federal troops. The “Black Hawk War” that is narrated in history texts was no more than a slaughter of Sauk farmers. The Sauks tried to defend themselves but were starving when Black Hawk surrendered under a white flag. Still the soldiers fired, resulting in a bloodbath. In his surrender speech, Black Hawk spoke bitterly of the enemy:

You know the cause of our making war. It is known to all white men. They ought to be ashamed of it. Indians are not deceitful. The white men speak bad of the Indian and look at him spitefully. But the Indian does not tell lies. Indian do not steal. An Indian who is as bad as the white men could not live in our nation; he would be put to death and eaten up by the wolves … We told them to leave us alone, and keep away from us; they followed on, and beset our paths, and they coiled themselves among us, like the snake. They poisoned us by their touch. We are not safe. We lived in danger.

The Sauks were rounded up and driven onto a reservation called Sac and Fox.

Most Cherokees had held out in remaining in their homeland despite pressure from federal administrations from Jefferson on to migrate voluntarily to the Arkansas-Oklahoma-Missouri area of the Louisiana Purchase territory. The Cherokee Nation addressed removal:

We are aware that some persons suppose it will be for our advantage to remove beyond the Mississippi. We think other wise. Our people universally think otherwise .... We wish to remain on the land of our fathers. We have a perfect and origi nal right to remain without interruption or molestation. The 112 An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States treaties with us, and laws of the United States made in pursu ance of treaties, guarantee our residence and our privileges, and secure us against intruders. Our only request is, that these treaties may be fulfilled, and these laws executed.

A few contingents of Cherokees settled in Arkansas and what became Indian Territory as early as 1817. There was a larger migra tion in 1832, which came after the Indian Removal Act. The 1838 forced march of the Cherokee Nation, now known as the Trail of Tears, was an arduous journey from remaining Cherokee homelands in Georgia and Alabama to what would later become northeast ern Oklahoma. After the Civil War, journalist James Mooney inter viewed people who had been involved in the forced removal. Based on these firsthand accounts, he described the scene in 1838, when the US Army removed the last of the Cherokees by force:

Under [General Winfield] Scott's orders the troops were dis posed at various points throughout the Cherokee country, where stockade forts were erected for gathering in and hold ing the Indians preparatory to removal. From these, squads of troops were sent to search out with rifle and bayonet every small cabin hidden away in the coves or by sides of mountain streams, to seize and bring in as prisoners all the occupants, however or wherever they might be found. Families at dinner were startled by the sudden gleam of bayonets in the doorway and rose up to be driven with blows and oaths along the weary miles of trail that led to the stockade. Men were seized in their fields or going along the road, women were taken from their wheels and children from their play. In many cases, on turn ing for one last look as they crossed the ridge, they saw their homes in flames, fired by the lawless rabble that followed on the heels of the soldiers to loot and pillage. So keen were these outlaws on the scene that in some instances they were driv ing off the cattle and other stock of the Indians almost before the soldiers had fairly started their owners in the other direc tion. Systematic hunts were made by the same men for Indian graves, to rob them of the silver pendants and other valuables deposited with the dead. A Georgia volunteer, afterward a colonel in the Confederate service, said: "I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew."

Half of the sixteen thousand Cherokee men, women, and children who were rounded up and force-marched in the dead of winter out of their country perished on the journey.”

Stains Series: Quashquema/Nauvoo, quilling (paper craft) on paper, 9” x 9” unframed, 12.5” x 12.5” framed, 2021

The Wilson’s Early Ascension in the Mormon Church

On May 5, 1839, Guy Carlton Wilson, the third son of Bradley Barlowe Wilson Sr. And Mary Gill Wilson, was ordained a Seventy, of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, in Quincy, Adams County, Illinois. A Seventy is a priesthood office in the Melchizedek priesthood, also referred to as the high priesthood of the holy order of God in the Mormon Church.

Sixth months later, October 6 - 8, 1839, Bradley’s son Lewis Dunbar Wilson was chosen as one of the first High Councilors in the LDS Church; as quoted in the Church’s Doctrines & Covenants 124: 131-132, Sec: 131, “And again, I say unto you, I give unto you a high council, for the corner stone of Zion–“ Sec: 132, “Namely, Samuel Bent, Henry G. Sherwood, George W. Harris, Charles C. Rich, Thomas Grover, Newel Knight, David Dort, [Lewis] Dunbar Wilson--Seymour Brunson, I have taken unto myself. . .David Fullmer, Alpheus Cutler, William Huntington.”

The Wilson families also helped to build the Mormon Temple at Nauvoo.

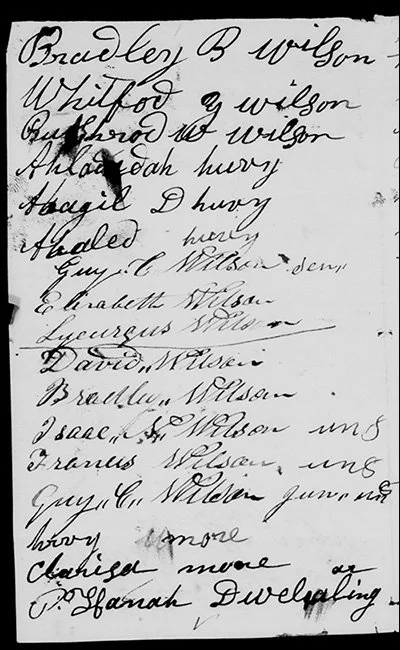

From the Nauvoo census in 1842

RIP Bradley Barlow Wilson Sr. and Mary Gill Wilson

Bradley Barlow Wilson Sr. and Mary Gill Wilson died in Nauvoo, Hancock County, Illinois. Mary died in 1841 and Bradley Sr. ‘died of numb palsy’ and was buried at Nauvoo in 1841. “He was 73 years old and had been a faithful Latter Day Saint for six- and one-half years.” Bradley and Mary then had thirty-nine grandchildren. Their sons became known as the ‘Seven Brothers’ after the exodus from Nauvoo.

Sources

Nauvoo Land and Records Office and The Pioneer Research Group of the "Winter Quarters" Nebraska area., "Early Latter-day Saints, A Mormon Trail Pioneer Database," database, Nauvoo Land and Records Office and The Pioneer Research Group of the "Winter Quarters" Nebraska area., Early Latter-day Saints, A Mormon Trail Pioneer Database (http://earlylds.com/getperson.php?personID=I28192&tree=Earlylds: accessed 17 October 2011), Bradley Wilson file contains sources for him; citing http://earlylds.com/getperson.php?personID=I36532&tree=Earlylds.

Frank Esshom, Prominent Men & Pioneers of Utah: COMPRISING PHOTOGRAPHS, GENEALOGIES, BIOGRAPHIES (Salt Lake City, Utah: UTAH PIONEERS BOOK PUBLISHING, 1913; http://www.archive.org/stream/pioneersprominen00esshrich#page/n5/mode/2up), 1253.

Gus Pendleton, findagrave.com, findagrave: Bradley Barlowe Wilson (http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSvcid=203047&GRid=31932733&df=np& : accessed 12 October 2011), gravesite of Bradley.

Brigham Henry Roberts, History of the Church, 7 Volumes (Salt Lake City, Salt Lake County, Utah: Deseret Book, 1976–1980), 1520, 2768.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, Beacon Press, 2014, pp.108 - 113