Strangers for Ancestors #8: The American Revolutionary War, 1776

As this week is 4th of July, this post chronicles my Wilson family’s trajectory during the era of the American Revolutionary War and my musings on their lives at the time and how that history relates to our contemporary landscape. The post also comes after two weeks that saw the United States Supreme Court continuing to gut protections for Americans and people who are discriminated against based on traits and circumstances they were born with and/or into - their race, sexual and/or gender identity, income levels, status as survivors of genocide. This past week’s rulings include the reversal of affirmative action, the ability for businesses to segregate and refuse service to someone or a group of people based on religious beliefs, and the denial of student loan forgiveness. The week before last was the one-year anniversary of the overturning of Roe vs. Wade; the Supreme Court also ruled against the Navajo/Diné nation - one of the 500+ tribes that this land we now call the United States was stolen from - for their water rights which were theirs to begin with, but also guaranteed by treaties signed in 1849 and 1868 between the tribes and the United States, and again broken by the United States.

All of these Supreme Court rulings are rooted in the deep racism, xenophobia, misogyny, religious fanaticism, and elitism the United States was founded on. However, while these values are embedded in much of the culture, it speaks volumes that we are now at a point in history in which the powerful work of American Indian tribes, anti-racists, feminists, the LGBTQIA+ community, labor, and social justice activists over the past 250 years is being overturned by the highest court in this nation. These Court decisions reflect a culture of hate and exclusion that calls to mind the fascist governments of the 1920’s - 40’s, such as Nazi Germany, Italy, and apartheid South Africa. We are entering into a new, yet familiar terrain, and while this past year has witnessed a number setbacks, we move forward knowing we are making deep inroads and ultimately we will prevail.

The Nipmuc peoples defending their ancestral land against the English settler-colonizers

Deliverance Wilson, the son of Joseph and Rebakah Wilson was born July 25, 1737 in Petersham, Massachusetts, the land stolen from the Nichewaug peoples. He married Sarah Smith, daughter of Henry Smith I and Mary Ann Smith of Petersham on February 9, 1764; Deliverance was 27 and Sarah was 21.

On November 13, 1764 their first child, Joel Wilson was born in Petersham. A year and a half later, their second child Levi Wilson was born on July 1, 1766. Two years later, on July 2, 1768 twins Deliverance Wilson Jr. and Sarah Wilson Jr. were born. There’s something sweet and endearing, yet funny about Deliverance and Sarah naming their twins after themselves. Their fifth child Bradley Barlow Wilson was born on October 11, 1769, and their sixth, Aaron Wilson was born about 1771. It’s possible Aaron didn’t survive long since there is no exact date provided for their birth and no record of their death.

Deliverance and Sarah moved their family to Rindge, Cheshire County, New Hampshire in 1771. Deliverance’s older brother Joseph Wilson Jr. and his wife Hannah Stone and their family joined them in 1773. Deliverance and Sarah are noted in the History of the Town Rindge as having “resided a few years in Rindge between 1771 and 1780. Their son Moses was bap. April 9, 1775.”

There’s no way of knowing what led to the families’ move to Rindge, though the timing coincides with growing tensions between the English settler-colonizers and the Crown/British Commonwealth around taxation, which had become impossible for many of the settlers, including the Wilsons as demonstrated by the number of letters the family members sent appealing for forgiveness of their taxes due to hardship. It’s understandable why the settler-colonizers would be incensed by the Crown’s demand for more taxes given that they were being used by the Monarchy to buildout England’s wealth through acts of genocide, the enslavement of Indigenous and Black bodies, and pillaging of the land. However what the settlers were either intellectually incapable of grasping, ignorant to, or what they knew, but could not, or would not acknowledge was that the whole settler-colonizer operation was a savage and inhumane act of playing God, and that religion was an easy and convenient justification for getting what one wanted, as well as a means for those in power to further enrich themselves.

Those living in America at that time chose “sides” and declared their loyalty to either the “Americans” or to the English (Loyalists). The War was fought between the Thirteen Colonies of America and the Kingdom of Great Britain.

The Wilson family sided with the “Americans.” Several of the sons of Joseph Wilson Sr. became American “minutemen” (temporary, not professional soldiers) who could be ready at a “minute’s” notice to fight to defend their homes and liberty (on the land they had stolen from the Nashua and Nipmuc peoples), on behalf of the Continental Congress of America. When the war began, the 13 colonies lacked a professional army or navy. Each colony sponsored local militia and militiamen who were lightly armed, had little training, and often did not have uniforms. Their units served for only a few weeks or months at a time because many settler-colonizers lived by farming and they could not leave their farms for long periods.

The Minutemen assisted the Continental Army in several Massachusetts battles, including: the Battles of Lexington and Concord (fought in Middlesex County, Massachusetts); the Battle of Bennington (fought in Walloomsac, New York); the Saratoga Campaign (fought in Upstate New York); and the Siege of Boston (fought in the area of Boston, Massachusetts).

Indigenous People’s Participation in the American Revolutionary War:

Two of the Indigenous tribes who participated in the American Revolutionary War were the Oneida Peoples and the Seneca Peoples. These alliances were not based on an allegiance to either the British colonizers or to the “American” settler-colonizers, these were strategies enacted to best protect their peoples and sovereignty.

As a lead up to the Declaration of Independence, Deliverance was one of the 148 signatories from the Colony of New Hampshire to sign a resolution in support of the status of the 13 colonies as a Continental Congress of independent states, dated April 12, 1776: to show our determination in joining our American Brethren in defending the lives, liberties and property of the inhabitants of the United Colonies, we the subscribers do hereby solemnly engage and promise that we will do the utmost of our power at the risqué of our lives and fortunes, with Arms oppose the Hostile proceedings of the British Fleets and Armies against the United American Colonies.

Deliverance is listed in Massachusetts soldiers and sailors of the Revolutionary War: a compilation from the archives as having served 17 days in the Revolutionary War as a Private with Captain Jotham Houghton’s company, which detached from Colonel Nathan Sparhawk’s 7th regiment. Service from November 3 to November 19, 1778. His brother Joseph Wilson Jr. is listed as having served as a Private in Captain John Wheeler's company of Minute-men, under Colonel Ephraim Doolittle's regiment which marched on the alarm of April 19, 1775 as part of the Battles of Lexington and Concord. He’s listed again as serving as a Private in Captain Benjamin Nye’s company, under Colonel Nathan Sparhawk’s regiment, serving September 20, 1778 to December 12, 1778.

Black Americans’ Participation in the American Revolutionary War:

Crash Course Black American History: When we talk about the American Revolution and Revolutionary War, the discussion often involves lofty ideals like liberty, freedom, and justice. The Declaration of Independence even opens with the idea that "all men are created equal." But it turns out, the war wasn't being fought on behalf of "all men." The war was mainly about freedom for white colonists, and liberty, justice, and the pursuit of happiness didn't apply to the Black people living in the British colonies. During the war, Black people took up arms on both sides of the conflict.

I realize it’s becoming more and more uncommon to have lived before the internet became so ubiquitous; a time when alternative sources for information and education were limited, especially if you lived outside of larger urban areas. People laugh or mock me when I talk about having loved Phil Donahue as a kid in Montana in the seventies and eighties, however, The Phil Donahue Show was my lifeline to discussions about feminism, race, sexual identity, trans identity, and HIV/AIDS, as I’m guessing it was for other kids too who lived in relatively homogenous communities, away from large cities.

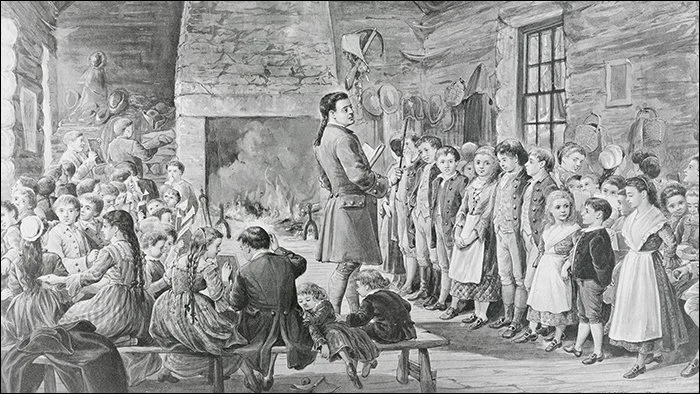

I raise this consideration of access because the educational resources and perspectives the settler-colonizers had available to them would have been limited, yet education was a high priority, especially for the Puritans who taught that those with faith could commune with God by reading the Bible.

The first laws governing education in America were passed by Massachusetts in 1642, a year before 7-year-old Benjamin Wilson arrived in America to serve the Bay Colony. The “Massachusetts Compulsory Attendance Law,” didn’t require children to go to school, but mandated that all Massachusetts heads of household were responsible for the education of all children living under their roof, including the children of servants and apprentices. “Education” meant instruction on reading, religion, and obedience. Additionally, because the English invaders approached the Indigenous and Black Peoples, land, and wildlife as things to be controlled and conquered rather than as living beings to be honored and respected, their descendants would be born to a life of conflict, resulting in generations of violence, trauma, and addiction. The impacts of this way of life would be far-reaching, including the introduction of plants and animals not suited for the North American continent, which created and continues to create havoc for the natural environment, as well as the repercussions of the deep racism that continues to divide this country.

Having been born in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, education would have been a priority to the Wilsons, this is supported by the listing of Joseph Wilson Sr. as a school committee member in the records of Petersham. Based on the following passage in the book History of the Town of Rindge, New Hampshire 1736 - 1874, chapter 13 Schools, it seems Deliverance might have had a learning disability/dyslexia:

The earliest settlers resided in this town twenty years before there were any public schools ; yet the youth who advanced to manhood at the close of this period were not uneducated. The parents were people of intelligence, often of considerable culture, and personally attended to the education of their own children ; and there were as many schools in town as there were families. The faithful instruction of parents to their children at the fireside must have been a pleasing feature of their home experience. Their school-books could not have been numerous, and probably their exchanges of readers less frequent than at present. Here in the wilderness these primitive instructors enjoyed an entire freedom from the importunities of book agents, and pupils conned their lessons from well-worn pages, and often from borrowed volumes.

Children, with their love of companionship, may have assembled at the house of some hospitable neighbor, whose ability to instruct would soon be recognized, and command remuneration; and private schools may have sprung from these informal gatherings.

Whatever may have been the system of instruction, the results are unmistakable. None were suffered to grow up in ignorance, and the many evidences of culture, made known in the lives of those whose only schooling was received at this time, are the substance of our knowledge of the education of that period.

William Russell, an infant when his parents removed to Rindge, was twenty years of age when the first public schools were instituted ; yet he was among the earliest of grammar-school teachers. Many instances of this character, too numerous and apparent to escape observation, might be cited. The " Association Test " was signed by all the citizens of this town that were not in the army. Their names are written in fair characters, in some instances with great elegance. Those who examine the original paper will find but one signature not plainly written ; but long before the name of Deliverance Wilson is made out, the practiced eye will discover that the illegibility arose from an unsteady nerve, rather than inexperience in the use of the pen. Among those in the army who did not here present a specimen of their handwriting, I know of but one who could not write his name. Asa Wilkins' middle name began with X, to which some friend would write "his mark." The wife of Joel Russell wrote her name in the same brief manner. Previous to the close of the century, no others have been found who could not write their names.

History of the Town of Rindge was written by Ezra S. Stearns in 1876. While 30 years before Norman Rockwell would illustrate the dreamworld of a white America in which there are always smiles and gratitude no matter the challenges, Stearns captures that same fairytale world of Once upon a time... Not surprisingly, Stearns was a politician from Rindge; he was a staunch member of the Republican party, and was elected to the House of Representatives 1864 - 70; and was elected to the Senate in 1876, the year the book was published.

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), Golden Rule, 1961. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2” x 39 1/2”. Story illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, April 1, 1961. Norman Rockwell Museum Collections.

However, it is this whitewashed narrative that we have been and continue to be fed by the dominant culture about the history of the United States; which today is most definitely not united, especially when it comes to the education of children. Based on the data available for book banning from PEN America, 34 states have banned books and the content for which they are most concerned about are books that include LGBTQ+ themes and books with People of Color as protagonists or as prominent secondary characters. In other words, the people behind the bans, don’t want their children to learn history or to learn about the experiences of people who are not like them, continuing the ethos of Xenophobia the country was founded on.

Megan Wilson, Stains Series: Skitchewaug/Springfield, quilling (paper craft) on paper, 9” x 9” unframed, 12.5” x 12.5” framed, 2021

In 1790, Deliverance, Sarah, and their family moved again to Springfield, Vermont. Deliverance is listed as one of the Freemen in Springfield in 1791 in the History of the Town of Springfield, Vermont, by C. Horace Hubbard and Justus Dartt, 1895. Deliverance and Sarah would have 10 children:

Joel Wilson, born November 13, 1764 in Petersham, MA

Levi Wilson, born July 1, 1766 in Petersham, MA

Deliverance Wilson Jr., born July 2, 1768 in Petersham, MA

Sarah Wilson Jr., born July 2, 1768 in Petersham, MA

Bradley Barlow Wilson, born October 11, 1769 in Petersham, MA

Aaron Wilson, born about 1771 in Petersham, MA

Moses Wilson, born April 9, 1775 in Rindge, MA

Dorcas Wilson, born in 1777 in Rindge, MA

Eunice Wilson, born 1781 in Rindge, MA

Hannah Wilson, born 1785 in Rindge, MA

Deliverance died on 15 December 1800, in Springfield, Windsor, Vermont, United States, at the age of 63; Sarah passed in Fairfax, Vermont in 1823 at the age of 80.

Sources:

Vital Records of Petersham, Massachusetts, To the end of the year 1849 (Worcester, Massachusetts: Franklin P. Rice, Trustee of the Fund (Systematic History Fund), 1904; http://archive.org/stream/vitalrecordsofpe00pete#page/n3/mode/2up), 57

Coolidge, Mabel Cook, for the Petersham Historical Society, Inc.. The History of Petersham Massachusetts: Incorporated April 20, 1754, Volunteerstown or Voluntown 1730-1733, Nichewaug 1733-1754. 1948. Hudson, Massachusetts, USA: Powell Press, 1948. Digital; http://www.archive.org/stream/historyofpetersh00cool#page/n7/mode/2up. openlibrary.org/internet archive. . : 2011. pp. 210, 219-220.

Stearns, Ezra S., History of the Town of Rindge, New Hampshire 1736 - 1874 with a Genealogical Register of the Rindge Families, Boston, Press of George H. Ellis, 1874, Digital; https://archive.org/details/historyoftownofr00stea/page/n5/mode/2up, pp. 88-89, 94-96, 108, 121-123, 125, 140, 171, 274

Massachusetts. Office of the Secretary of State, Massachusetts soldiers and sailors of the Revolutionary War: a compilation from the archives, Volume 17, 1896. Digital; file:///Users/Jolly/Downloads/ocm12601336-1908-v.17%20(2).pdf; pp. 561, 572-73.

Hubbard, Horace C. and Dartt, Justus, History of the Town of Springfield, Vermont with a Genealogical Record, 1752-1895; Digital; https://archive.org/details/historytownspri00dartgoog/page/n8/mode/2up pg. 525

Roos, David, History, What Was School like in the 13 Colonies, June 8, 2023; Digital; https://www.history.com/news/13-colonies-school

Pen America, Book Bans, 2023; Digital; https://pen.org/report/banned-in-the-usa-state-laws-supercharge-book-suppression-in-schools/