PUBLISHED WRITINGS

The Gentrification of Our Livelihoods: Everything Must Go, Stretcher, 2014

Megan Wilson began her writing career as a staff writer for the Daily Emerald when she was an undergraduate student at the University of Oregon in the early nineties. Wilson continued to use her writing skills when she began doing grant writing for the Samaritans of Boston, a suicide prevention agency that served as her first job out of college. Wilson has continued to write and use writing in her work as: 1) an arts & cultural critic; 2) a development, planning, management, & visibility consultant for non-profit organizations; and 3) a creative writer.

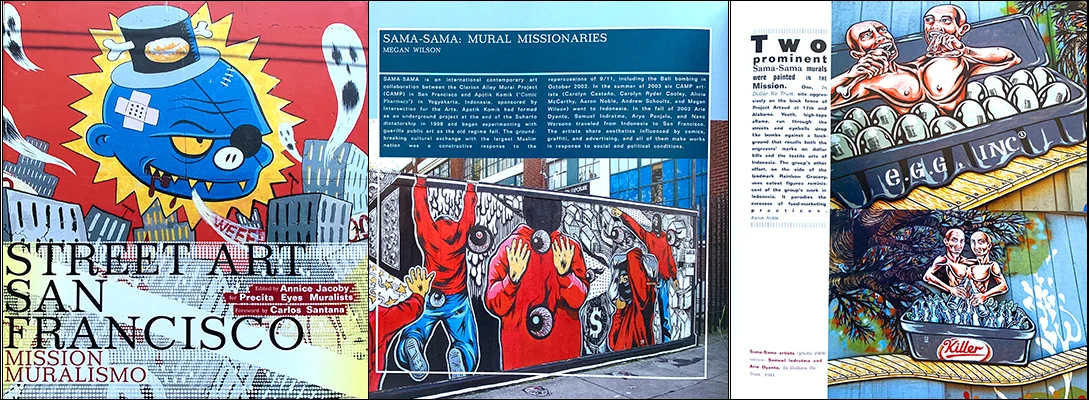

Wilson co-founded the San Francisco-based arts Website www.stretcher.org. She was the weekly art writer for the San Francisco Bay Guardian 2000 - 2001, and In 2001-2002 she wrote weekly art reviews for Digital City. Her writings have appeared in stretcher.org, afterimage, "Up The Staircase Quarterly," Digitalcity, Public Art Review, and Art Practical; in Reimagine: The National Journal About Race, Poverty, and the Environment; and in the books Street Art San Francisco Mission Muralismo (edited by Annice Jacoby with Forward by Carlos Santana); Sama-Sama/Together, published by Jam Karet Press in 2006; and in the upcoming book Bangkit/Arise to be published by Semangat! Press in 2020.

From 2011 to 2016, as part of the Clarion Alley Mural Project (CAMP), I painted five large murals on the alley.

All five murals spoke, directly or indirectly, to the critical need for a fundamental shift away from capitalism that puts profit before all else and negatively impacts the health, environment, and wellbeing of all.

The response to each of these public works was, and continues to be overwhelmingly positive. I still meet people, who when they learn that I work with CAMP, will pull out their phones and show me an image of one or more of these murals, often being used as their screensaver. I’m also regularly contacted by students and academics who want to interview me, write about the murals, and/or use images of the work in books or articles.

Thankfully too, the murals rarely got tagged with graffiti, and when they were, it was fairly innocuous and easy to repair, with the exception of CAPITALISM IS OVER! If You Want It, which I encouraged during its final month as part of its conceptual framework.

While flattering to have one’s work hit a nerve among diverse and global audiences, more important to me is that the attention coincides with a shifting consciousness on the views of capitalism among youth.

According to a comparison of Gallup polls between 2010 and 2018, in 2010, 68 percent of youth ages 18-29 polled had a positive view of capitalism; in 2018 that percentage had dropped 23 points to 45 percent. Additionally in 2016, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) had 5,000 members. In 2019 that number has grown to 56,000.

In fall 2018, I replaced the “Stop The Corporatocracy” mural with one that now reads “End Apartheid B.D.S.” in large stylized letters in the foreground with slightly smaller, narrower text recurring in the background that reads “Boycott Divest Sanction.” The entire mural and pavement in front are adorned with my signature flowers. Like the five other murals, this one advocates for social justice and speaks to global systems of colonialism, imperialism, and development. More specifically, the work speaks to Israel’s oppression of Palestinians as an apartheid state. This claim is not just my personal belief; in 2017 the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) released a report on the treatment of Palestinians by Israel that concluded: “The weight of the evidence supports beyond a reasonable doubt the contention that Israel is guilty of imposing an apartheid regime on the Palestinian people.” Additionally, the mural directly advocates for the use of a non-violent economic response to human rights abuses.

I read Maw Shein Win’s latest chapbook Score and Bone (Nomadic Press) during the two weeks before the 2016 election. It was a favorite escape from the daily barrage of crude insanity. I’d turn off my computer and phone, snuggle up with my cat and cherish spending the next hour or so in a rich terrain of unexpected scenes and stories. Unlike the real world around me that has come to muddle my mind and crush my spirit daily, the words and worlds traversed inScore and Bone are vivid and alive with pleasure, pain, and an absurdity that captures the human experience with a playfulness rather than defeat.

Score, the first section of poems is presented as a series of films. While each ‘film’ fits within one page, some are considered Shorts, others are Random Film Shots, Close-Ups, or Dialogues. There are Two Documentaries, the Score, The Treachery of Images, and The Missing. All are mesmerizing and stripped down to the core in a way that leaves the reader/observer lingering on the beauty and power of the elements Win provides.

At times I found myself becoming a collaborator, adding to the narrative or contextualizing a scene within a memory from my childhood or travels.

CONTINUE READING …

Gentrification of Our Livelihoods: Everything Must Go …

Preface: When I began researching and writing The Gentrification of our Livelihoods in early March 2014 one of my primary interests was the impact that the collaboration between Intersection for the Arts and developer Forest City’s creative placemaking 5M Project is having on the existing communities that have invested in and called the South of Market home prior to the tech booms. Having worked with many community-based organizations within the SoMa community for the past 18 years, I’ve had deep concerns about the development’s impact for the neighborhood and its impact on the future of Intersection.

However, I would not have predicted the announcement that Intersection made on May 22nd to cut its arts, education, and community engagement programs and lay off its program staff would come as soon as it did. What began as a reflection on the shortcomings of creative placemaking as a tool for economic development and its implications on gentrification and community displacement has become a cautionary tale for arts and community organizations to question and better understand the potential outcomes of working with partners whose interests are rooted in financial profit.

Over the past two months I’ve spoken with many of the stakeholders involved with the 5M development, as well as the creative placemaking projects that are helping to shape the changes in the culture and landscape throughout San Francisco, these include: Deborah Cullinan, former Executive Director, Intersection for the Arts; Jamie Bennett, Executive Director, ArtPlace America; Angelica Cabande, Executive Director, South of Market Community Action Network (SOMCAN), Jessica Van Tuyl, Executive Director, Oasis For Girls, April Veneracion Ang, Senior Aide to Supervisor Jane Kim, District 6 and former Executive Director of SOMCAN; Tom DeCaigney, Director of Cultural Affairs, San Francisco Art Commission; Bernadette Sy, Executive Director, Filipino-American Development Foundation (FADF); Josh Kirschenbaum, Vice President for Strategic Direction, PolicyLink, and an anonymous source within Forest City Enterprises.

I recommend reading the in-depth interviews with the majority of these participants. Their input helps to augment and present a fuller understanding of the complexities, concerns, and possibilities of the stories and information provided in the article. Please click on the links below to read:

Deborah Cullinan, Executive Director, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, former Executive Director, Intersection for the Arts

Jamie Bennett, Executive Director, ArtPlace America

Angelica Cabande, Executive Director, South of Market Community Action Network (SOMCAN)

Jessica Van Tuyl, Executive Director, Oasis For Girls

April Veneracion Ang, Senior Aide to Supervisor Jane Kim, District 6 and former Executive Director of SOMCAN

Tom DeCaigney, Director of Cultural Affairs, San Francisco Art Commission

Home, (2009) Essay originally written for Street Art San Francisco Mission Muralismo (edited by Annice Jacoby with Forward by Carlos Santana)

Home/Casa (ground) by Megan Wilson, 2000; and I Know Which Way the River Flows (wall) by Brian and Jasper Tripp, 1998; Clarion Alley, Mission District, San Francisco

Home

In Buddhist teaching, suffering is explained as a result of the attempt to cling to permanence. For Buddhists, loss and impermanence are things to be accepted rather than causes of pain and grief -- nothing lasts, nothing stays the same.

In the late nineties/early millennium the Bay Area was the epicenter of a massive transformation brought about by the dotcom boom and the new economy. Commercial rents in San Francisco skyrocketed to $80/square foot, long-time residents were displaced (by 1998 two-thirds of the residents in the Mission District were new arrivals), and 1,400 luxury lofts were approved for development in the South of Market District – rashly, as it turned out: the vacancy rate was at 45% by 2001 (year of the dotcom bust).

Many watched as the neighborhoods they had spent years building were dismantled and replaced by dotcom startups headed up by perky twenty to thirty-year-olds, often straight out of college or graduate school and seemingly under the impression that San Francisco was just another college campus. The Mission District in particular felt like a big kegger with hordes of loud, drunken frat kids pouring out onto the streets nightly from the trendy upscale venues that were popping up all along Valencia Street at the time.

In the arts community, we saw the departure of a number of artists and arts spaces. Four Walls, Scene/Escena, and ESP all closed their doors and plans were in the works for the demolition of the headquarters of the Clarion Alley Mural Project to make way for condo development, potentially ending a 7-year old organization that had given many artists the opportunity to create a public work (1). Developers were also looking at the Redstone Building, (historically the old Labor Temple) which houses The Lab, Theatre Rhino, Whispered Media Video Activist Network, Luna Sea, and seven artists' studios (including mine) – in addition to a number of non-profit organizations. (2)

Home 1996 – 2008 was a site-specific installation/environ-ment that utilized the interior space of my home to explore and challenge notions of comfort and protection, private and public, and the boundaries between art/life/architecture/ design. The title is a bit of misnomer because I actually started working on the project in 2004 (the dates reflect the years that I lived at the residence).

In November 2008, I officially opened Home to the public for 4 weeks. The installation was open 1:00-5:00pm Wed-Fri each week. The month also included a series of events and digital projections: 1) Eliza Barrios curated a series of video works that were projected nightly onto a window scrim that was best viewed from across the street; 2) I hosted 2 dinner salons that engaged participants in discussions of home, environment, global forces that have reshaped how interior space is viewed, and contemporary trends in exhibiting and experiencing art; and 3) I invited 3 artists - Gordon Winiemko, Lise Swenson, and Maw Shein Win - to each host an evening of work related to the context of the project.

Verner Panton, Visiona 2, 1970

Development of Home 1996-2008

When I first began the Home project in 2004 I had just finished a 2-year international exchange project that had exhausted me physically, mentally, emotionally, and creatively. There was also a considerable degree of anxiety in the air because of the Iraq war and the crimes of the Bush administration. I was having a difficult time mustering up the energy to make art or to even leave my apartment if I didn’t have to; yet I also knew I couldn’t continue to lie on my couch watching bad network TV. I decided I would use my discomfort as an opportunity and make work that spoke to this experience and to my interest in the boundaries between art, life, architecture, and design by turning my apartment into a living artwork that could evolve organically.

I began experimenting with vintage curtains I had bought at a second hand store, cutting out the flower designs of the textiles and pinning them on the bathroom walls. While I wasn’t sure what the meaning of this was, I liked it, and more importantly, I was okay with not knowing and allowing my process to be loose and intuitive. This followed with selecting a color palette and painting the walls and the ceilings of the bathroom, kitchen, and hallway. Over time I expanded into almost every room, using a variety of materials and processes to transform the space. As I continued to work, it became clearer to me that I was creating a world that would attempt to redefine my reality. I used the aesthetics of my childhood in an effort to create a warm and safe environment that contrasted how I’d actually experienced my home growing up. I used traditional craft-based materials to adorn the space and approached the process as conceptual fine art, knowing that it would likely be dismissed as simply home décor. I wanted to present the project publicly and create a place for conversations about the meanings and interpretations of “home” and “art.”

Additionally, I began to contextualize the project in a larger framework and acknowledge artists who had inspired me: Home 1996 – 2008 referenced and borrowed ideas from artists such as Dadaist Kurt Schwitters, who erected the Merzbau, a real-life expressionistic interior, in his studio in Hanover, Germany; feminists Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, who spearheaded Womanhouse - a series of fantasy environments exploring the various personal meanings and gender construction of domestic space; and conceptualist David Ireland, whose work “has a visual presence that makes it seem like part of a usual, everyday situation;” architects and designers such as Verner Panton, who created floor-to-ceiling and back-down-the-walls-to-the-floor, psychedelic interiors in the sixties and seventies, César Manrique, who designed Star Trek-like party spaces; and communities of West Africa, where each year after harvest, women gather to restore and paint their mud dwellings which are washed away by rain every year.

Continue Reading …

San Francisco International Airport

by Megan Wilson

Feature for Public Art Review

Spring 2002

Rigo 99, Initial proposal for the San Francisco Art Commission for the San Francisco Airport, 1998

I remember the first time I really noticed the public space of an airport. About fifteen years ago, I was walking through a corridor at Chicago O’Hare and encountered a light installation by Michael Hayden in the United Airlines terminal that created the sense of a tunnel. I loved it. The atmosphere it created seemed so sophisticated and alive—different from how I was accustomed to experiencing airports as cold, boring, and generic. The installation was later removed due to negative feedback.

It’s hard to say what my response to this work would be now, but what was important then was the awareness it brought to my understanding of public space. After this pleasantly surprising incident, I became much more attuned to how I felt in the public domain of air travel. As an artist, this awareness has become almost second nature. For many people, however, the impact of civic surroundings on one’s inner state is probably not understood in terms of deliberate design. Yet, the power of such constructs can mean the difference between beginning a trip with hope and great expectations or with stress and anxiety. It can also mean the difference between perceiving a city as dull and cramped versus lively and engaging.

In 1994 the San Francisco International Airport undertook a $2.4 billion expansion of its facilities to meet the demands of increasing international air traffic, including a new 2.5 million square foot (the equivalent of 35 football fields) International Terminal, the largest such facility in North America. As part of this large project, the Airport Arts Program commissioned seventeen new works of art through the San Francisco Arts Commission in accord with the city’s “percent for art” ordinance, which provides an art enrichment allocation equal to 2 percent of a new or renovated civic structure’s construction cost. The total budget for the art (including administration) was $11.1 million, with individual pieces ranging in cost from $91,389 to $1,638,637. Included are works by Vito Acconci, Juana Alicia and Emmanuel Montoya, Squeak Carnwath, James Carpenter, Enrique Chagoya, Lewis deSoto, Viola Frey, Su-Chen Hung, Mildred Howard, Joyce Kozloff, Rupert Garcia, Carmen Lomas Garza, Ann Preston, Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel, Rigo 02, and Keith Sonnier.

The result is impressive. Seven of the works are large-scale installations that have been integrated into the architecture. These include California artist Ann Preston’s You Were in Heaven, an elegant, cloud-like, sculptural wall piece made from fiberglass and installed on five, sixty-foot curving concave walls. The work was chosen for its relaxing and rejuvenating effects as a respite between a traveler’s long flight and upcoming immigration lines. Artist James Carpenter worked with the main terminal’s design team to develop a series of light-diffusing tensile sculptures that are integrated with the skylights and central trusses of the main terminal roof. The billowing structures reinforce the idea of the new International Terminal as a visual metaphor for flight. San Francisco-based artist Su-Chen Hung created an installation on the arrivals level that incorporates colloquial greetings in over one hundred languages cast in five-foot prismatic glass slabs.

CLEARING THE AIR

Code 33

by Suzanne Lacy, Julio Morales, Unique Holland, David Goldberg, Michelle Baughan, Raul Cabra & Patrick Toebe

Intersection of the Arts

San Francisco, California

May 2-June 16, 2001

In 1998 a group of artists and activists led by Suzanne Lacy and T.E.A.M. (Teens + Education + Art + Media) initiated a project with youth and police in Oakland, California to clear the air and open up dialogue between the two disparate groups. Over a two-year period "Code 33" came to be the term for an ambitious, large-scale collaboration whose participants included 150 youth, the Oakland Police Department, the Oakland Mayor's Office, the Community Probation Program of Alameda County, Oakland Sharing the Vision (a neighborhood revitalization task force), California College of Arts and Crafts, the Alameda County Office of Education and the Oakland Museum.

Most recently, the project was presented as an installation by Lacy and "Code 33" collaborators Julio Morales, Unique Holland, David Goldberg, Michelle Baughan, Raul Cabra and Patrick Toebe at Intersection for the Arts in the Mission District of San Francisco. To understand the implications of the exhibit as "another platform to address immediate social issues and to build community through the experiential, experimental art process" it is important to know the circumstances and the event from which this installation grew (1).

"Code 33" is a police term for "emergency, clear the air." Depending on the source, the interpretation has ranged from addressing a volatile situation in the name of public safety to creating a cultural environment of racial profiling and stereotyping that has marked young people as targets of public scrutiny and legislative punishment. In Oakland one quarter of the residents are youths. One of the predominant fears among this population is of the police, and not without good reason. The arrest rate for Oakland's kids and young adults has grown by 35% over the last 10 years, and in March of 2000 California passed Proposition 21. This measure increases the number of youths tried in adult court, disables the prudence of judges and corrections professionals to determine appropriate interventions and allows youths to be liable for crimes committed by others if they are deemed gang members (defined as an informal group of three or more people).

"Code 33" was initially manifested as a highly produced pop performance spectacle with 150 youth participants and 100 police officers that took place on October 7, 1999 on the rooftop of a parking garage. An audience of roughly 1000 community members looked on and listened in as youths and police engaged in a dialogue exploring the realities and stereotypes experienced and perceived by both.

STRETCHER.ORG

Stretcher.org is-was an online publication that provides a voice to the visual arts and culture in the Bay Area, while connecting with creative communities internationally. Currently, the publication is only periodically updated and serves more as an archive.

The idea for Stretcher grew out of a recurrent conversation between Megan Wilson and Glen Helfand. They recognized a lack of Bay Area visual art publications that provided broader critical discourse on art and its connection to other cultural disciplines (politics, economics, personalities, and socio-cultural phenomena). They decided to create a publication that would address this need. Amy Berk, Andy Cox and David Lawrence were invited on board to help create the initial framework for Stretcher and were later joined by Ella Delaney, Cheryl Meeker, Tonita Abeyta, and Meredith Tromble. The first year of development saw several transitions, including the departure of Cox to pursue personal projects and Wilson’s 8-month leave to also complete outside projects. Stretcher.org was launched on June 5, 2001. Wilson continued to work with Stretcher as an editor and contributing writer through February 2002. Stretcher continued to thrive and transform under the direction of Amy Berk, Ella DeLaney, David Lawrence, Cheryl Meeker, and Meredith Tromble. The publication was updated regularly with new reviews, essays, artists' projects, and updates from around the world until 2015.

Articles for Stretcher:

The Gentrification of Our Livelihoods: Everything Must Go (2014)

Selamat Datang! Welcome! (2002)

Review: Tiara Dame Ruth Sirait: Sweet Lolly, (2002)

Worlds In Collision at SFAI, (2001)

Review: Sophie Calle: Public Spaces - Private Places, (2001)

SAN FRANCISCO BAY GUARDIAN

For two years - 2000-2001 Wilson was the weekly Arts columnist for the San Francisco Bay Guardian. Selected articles include: